In recent years, with the rise of the pre-trained Transformer [1] models, we are switching (or using in hybrid fashion) traditional models such as BM-25, RankSVM, and LambdaMART with deep neural models. These models can be used for retrieval and (re-)ranking. In this post; I am going to introduce some of the Neural Information Retrieval models and show some practical use cases. However, this post does not include all of the methods in the literature, only the ones that I learned (heavily based on contrastive learning models).

Introduction

Neural methods in Information Retrieval (IR) are started to be used more often, due to rise of the pretrained Transformer models such as BERT [2], RoBERTa [3], T5 [4] etc. The power of these models is coming from the self-attention mechanism and the massive size of the pre-training corpus. These models are used to produce high quality contextualized dense embeddings for retrieval, or used to obtain interacttion between query and document for (re-)ranking. Comparing to lexical traditional models, these models are useful to capture complex semantic structure of queries and documents as well as lexical structure. Besides that, these models can be used in few-shot or even zero-shot settings, and overcome cross-lingual retrieval scenarios.

Many approaches modify pre-trained models for information retrieval. For example, we can use a single BERT as a retrieval model: extract dense embeddings of documents, get the query embedding at inference time, and search. This approach would be successful, however, we can say introducing some kind of relationship between queries and documents would inject more information into our model intuitively. With that motivation, literature has been designing powerful contrastive learning models for different problems in information retrieval.

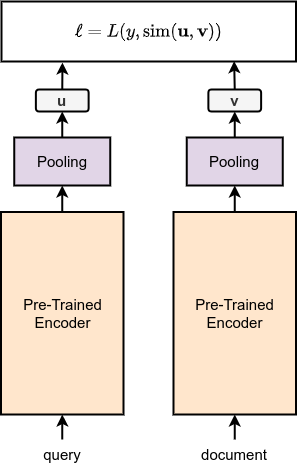

Using Siamese BERT for Retrieval

Sentence Transformers are introduced in the paper called Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks [5]. The idea is simple yet efficient: use siamese or triplet BERT networks and optimize them by metric learning. Authors used three objective function for three different setup:

SNLI dataset consists of a premise, a hypothesis, and a label (entailment, neutral, and contradiction). In this setting, premise and hypothesis is given to the encoder and embeddings \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{u}\) are produced. Then, the cross entropy loss is calculated between the class label and

\[l = \text{softmax}(\mathbf{W_t} \cdot \lbrack \mathbf{u}; \; \mathbf{v}; \; \mid \mathbf{u} - \mathbf{v} \mid \rbrack)\]STS dataset consists of two sentences and a numeric label that represents the similarity between two santences, in the range of 1 to 5. In this setting, premise and hypothesis is given to the encoder and embeddings \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{u}\) are produced. Then, a cosine similarity loss is calculated by MSE

\[\text{MSE} = \frac{1}{B} \sum_{i=1}^{B}\left(L_i - \frac{\mathbf{v}_i \cdot \mathbf{u}_i} {\left\| \mathbf{v}_i\right\| _{2}\left\| \mathbf{u}_i\right\| _{2}} \right)^2\]where \(B\) is batch size.

Triplet Network can be used for different purposes. Authors used triplet sentence transformer for Wikipedia Sections Distinction dataset. It has an anchor \(a\), a positive \(p\), and a negative \(n\) example. The optimization becomes a margin loss to minimize the distance between \(a\) and \(p\), and maximize the distance between \(a\) and \(n\):

\[\max(\left\| \mathbf{v}_a - \mathbf{v}_p\right\| _{p} - \left\| \mathbf{v}_a - \mathbf{v}_n\right\| _{p} + \varepsilon, 0)\]where \(\left\| \cdot \right\| _{p}\) denotes the \(p\)-norm. \(\varepsilon\) ensures that \(\mathbf{v}_p\) is at least \(\varepsilon\) closer to \(\mathbf{v}_a\) than \(\mathbf{v}_n\)

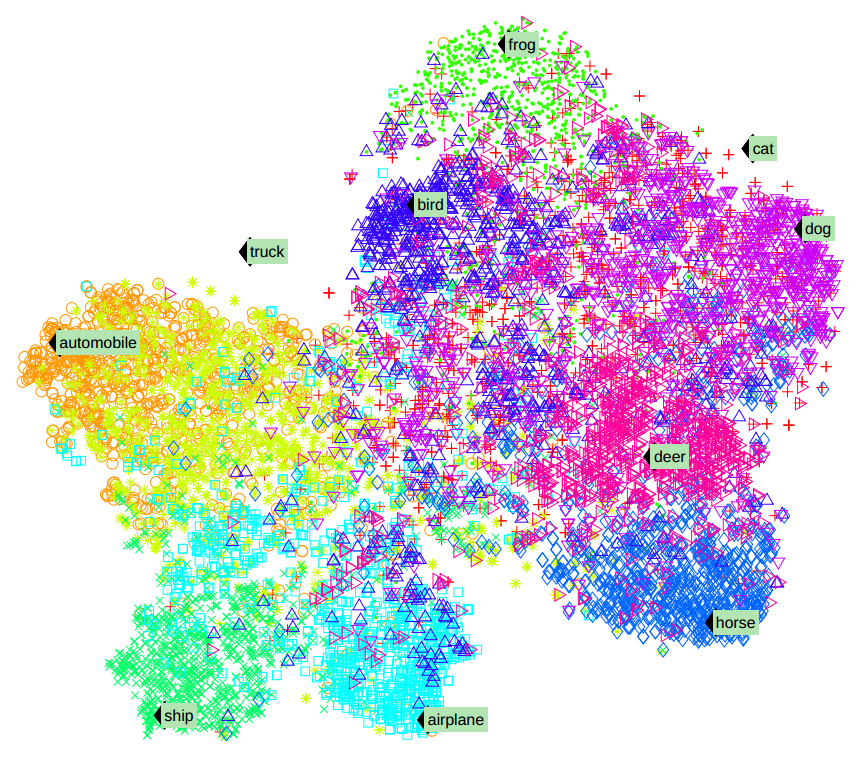

SimCSE

A remarkable contribution came from the paper called SimCSE: Simple Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings [6]. In the SimCSE paper, authors proposed unsupervised and supervised approaches to produce sentence embeddings. Each method leverages positive and negative examples. In unsupervised setting, given an input \(x\), the positive is obtained by applying dropout operation to \(x\). In simple terms, \(x\) is passed to the transformer encoder twice (which has dropout rate \(p=0.1\)), and embeddings with different dropouts are obtained. If we denote pair embeddings as \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{v}^+\), the objective becomes minimize the negative log-likelihood loss:

\[\ell = - \sum_{i=1}^B \log \frac{\exp(\text{sim}(\mathbf{v}_i, \mathbf{v}_i^+))/\tau}{\sum_{j=1, j \neq i}^B \exp(\text{sim}(\mathbf{v}_i, \mathbf{v}_j^+))/\tau}\]where \(B\) is the batch size. In the denominator, \(\mathbf{v}_j^+\) can be seen as negative example of \(x\), because we are trying to maximize the probability of positive example against over all \(\mathbf{v}_j^+\). Negative examples are chosen from other sample’s positive examples in the batch. This loss sometimes is called multiple negatives ranking loss.

In supervised form, there is nothing different. Given a labeled dataset, triplets are \((x_i, x_i^+, x_i^-)\). Objective becomes:

\[\ell = - \sum_{i=1}^B \log \frac{\exp(\text{sim}(\mathbf{v}_i, \mathbf{v}_i^+))/\tau}{\sum_{j=1, j \neq i}^B \left(\exp(\text{sim}(\mathbf{v}_i, \mathbf{v}_j^+))/\tau + \exp(\text{sim}(\mathbf{v}_i, \mathbf{v}_j^-))/\tau \right)}\]Supervised SimCSE outperforms SBERT in all STS benchmarks.

Knowledge Distillation for Multilinguality

In the paper called Making Monolingual Sentence Embeddings Multilingual using Knowledge Distillation, authors proposes a practical idea (but not novel). For set of translation pairs \((s_i, t_i)\), the aim is to train a new student model \(M_{\text{student}}\) to satisfy the conditions \(M_{\text{student}}(s_i) \approx M_{\text{teacher}}(s_i)\) and \(M_{\text{student}}(t_i) \approx M_{\text{teacher}}(s_i)\). In the work, authors used XLM-R as student model and SBERT model as teacher model.

The student model \(M_{\text{student}}\) is trained by mean-squared loss:

\[\frac{1}{B} \sum_{i=1}^{B} \left[ ( M_{\text{teacher}}(s_i) - M_{\text{student}}(s_i))^2 + ( M_{\text{teacher}}(s_i) - M_{\text{student}}(t_i))^2\right]\]Using Sentence Embeddings for Retrieval

A contrastive model that is trained on (query, positive document) pairs or (query, positive document, negative document) triplets can be used for retrieval. The idea is simple: after the training of the model, embeddings of documents are stored to the database. Then, at inference time, compute the query embedding via trained model, then retrieve the top-\(k\) relevant apps using a similarity function.

However, calculating similarity between a query embedding and all document embeddings (Google has more than 25 billion documents) is not practical. Response from a search engine should be lower than 100 miliseconds. For that purpose, we generally use approximate nearest neighbor search. Approximate search consists of specific index structures, clustering, parallelism etc. Luckily, there are a lot of approximate search libraries implemented by software engineers such as faiss, annoy, spann, and scann etc.

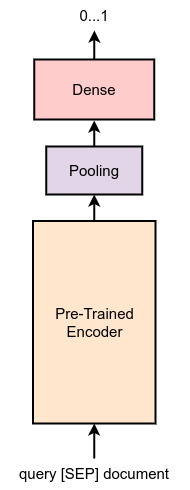

Cross-Encoders for (Re-)Ranking

After the retrieval, we rank (or re-rank) the retrieved documents and sort them by some criterion (or by a specific score). Their usage usually achieves superior performance in search systems. Comparing to dual-encoders (SBERT, SimCSE, etc.), Cross-Encoders generally consists of a single encoder. This encoder takes an input, which is the concatenation of query and relevant document. If choose BERT model as cross-encoder, the input becomes “[CLS] query [SEP] document [SEP]”.

The optimization of the Cross-Encoders generally done by passing the representation of [CLS] token into a linear function. In simple terms, this computes the relevance score. For example, we can approach this problem as binary classification, whether the given document is relevant with given query:

\[\ell = - \sum_{j \mid y_{ij}=1} \log(s_{ij}) - \sum_{j \mid y_{ij}=0} \log(1 - s_{ij})\]where \(y_{ij}\) is target, \(s_{ij}\) is predicted score for the pair \(i\) and \(j \in D_i\) where \(D_i\) is candidate documents. This approach is sometimes called pointwise cross entropy loss because it is calculated for each query-document pair independently.

Another approach is called pairwise softmax cross entropy loss, which is defined as

\[\ell = -\log \frac{\exp(s_{q_i, p_i^+})}{\exp(s_{q_i, p_i^+}) + \sum_{j=1}^{B} \exp(s_{q_i, p_{i_j}^+})}\]Cross-Encoder Implementation in SBERT

In SBERT library, Cross-Encoders are trained by point-wise loss, which is implemented using binary cross entropy loss with logits:

\[\ell(q, d) = L = (l_1, l_2, ..., l_B)^T\] \[l_i=-w_i \cdot (y_i \cdot \log(s_i) + (1-y_i) \cdot \log(1-s_i))\]where \(B\) is the batch size.

Augmented SBERT

An extremely powerful method in search scenarios is using cross-encoder as an annotator for your scarce data. In the paper called Augmented SBERT: Data Augmentation Method for Improving Bi-Encoders for Pairwise Sentence Scoring Tasks [7], authors proposed a method called Augmented SBERT. The idea is simple. Suppose that you have a relatively small-sized labeled dataset (gold data) and large-sized unlabeled dataset (silver data). Each sample consists of a pair and a continuous label between 0 (indicates not relevant), and 1 (indicates strong relevancy). In Augmented SBERT, there are 4 steps:

- Train a Cross-Encoder with the gold dataset.

- Label the silver dataset.

- Concatenate gold and silver datasets.

- Train a Dual Encoder.

In practice, it is not that hard to find a unlabeled sentence pair dataset. For example, your current search system have large amount of query session logs, you can prepare a gold dataset based on a small set of click frequencies, and you can prepare a silver dataset with large set of click frequencies.

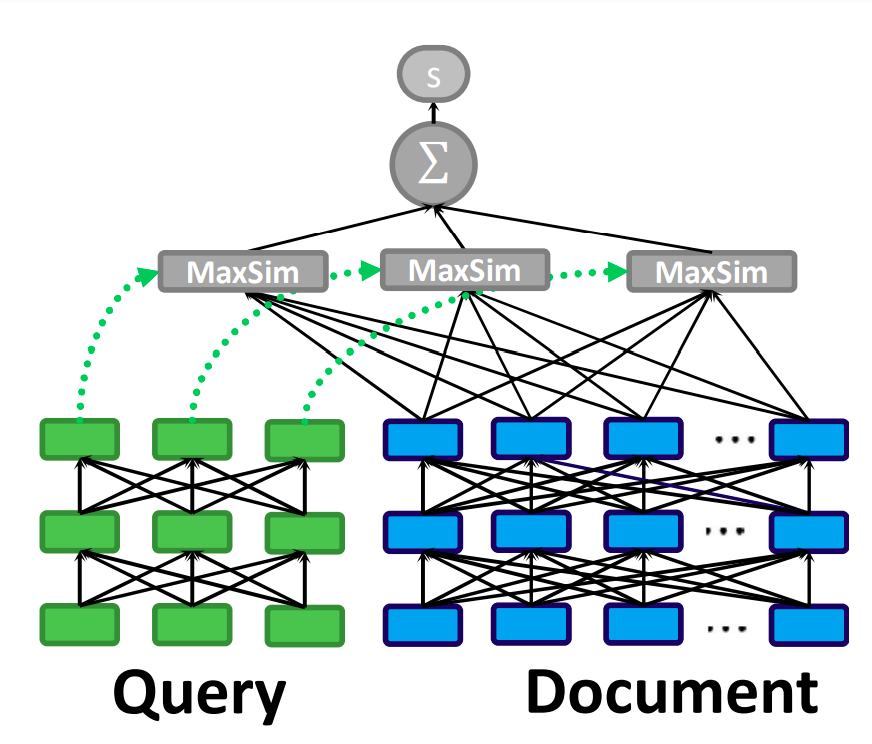

ColBERT

ColBERT model [8] can be used for re-ranking and retrieval. The practical idea behind ColBERT is, you do not have to pass query and documents to re-ranker model at inference time. Due to its late-interaction mechanism, we save the document embeddings and use them at inference time to score. The late-interaction module can be seen as dual-encoder: query and document are passed to the encoder independently, for each token representation, “MaxSim” operation is calculated:

\[S_{q, d} = \sum_{i \in \mathbf{v}_q} \max_{j \in \mathbf{v}_d} \mathbf{v}_{q_i} \cdot v_{d_j}^T\]Batched operations required padding. In ColBERT, instead of using “[SEP]” as padding token, authors used “[CLS]” token. They claims that this method acts like a query augmentation, learning to expand queries with new terms or to re-weigh existing terms [8].

Since we are storing the document embeddings in ColBERT, it is possible to use the model as end-to-end retrieval model with aprroximate search.

Multi-Stage Document Ranking with BERT

A multi-stage ranking system is hierarchical ranking system. More formally, in a document space \(D\), you retrieve \(R_0\) documents with a retriever (can be BM25 or a dual encoder), then you rank the retrieved documents and select the top-\(k_1\) of them: \(R_1\). The last step is re-ranking \(R_1\) documents and select the top-\(k_2\) documents. After applying retrieve, rank and re-rank steps, \(R_3\) documents are shown in the search.

In the paper called Multi-Stage Document Ranking with BERT, authors proposes a mono-encoder (pointwise) for ranking and a siamese-encoder for re-ranking (pairwise). The retrieval algorithm is selected as BM25 algorithm, which means the overall search system is hybrid.

After retrieving \(R_0\) documents, mono-BERT is optimized as a binary relevance classifier. Query and documents are concatenated with “[SEP]” token, and the “[CLS]” representation is fed to the classification head:

\[\ell_{\text{mono-BERT}} = - \sum_{i} y_i \cdot \log(s_i) - (1 - y_i) \cdot \log(1 - s_i)\]where \(s_i\) is the predicted score.

The last step is using siamese-BERT as pairwise. top-\(k_1\) of \(R_1\) is selected and re-ranked. In \(R_1\) each document \(d_i\) has a ranking score with \(q_j\). To be more formal, we have ranking score set, which is defined as \(S = \{r_{i, j} \mid i \in \mid Q \mid, j \in R_1\}\). So, we can define a set which represents relevancy of document \(d_i\) over \(d_j\): \(P = \{p_{i,j} \mid i \in R_1, j \in R_1, i \neq j \}\). The input is now concatenation of query and document pairs with “[SEP]” token, and the “[CLS]” representation is fed to the classification head. The pairwise loss is defined as:

\[\ell_{\text{siamese-BERT}} = - \sum_{i, j \mid r_i > r_j} \log(p_{i, j}) - \sum_{i, j \mid r_j > r_i} \log(1 - p_{i, j})\]The final re-ranking score of document \(i\) is calculated by different aggregation scores, for example sum is defined as \(s_i = \sum_{j} p_{i, j}\) and binary is defined as \(s_i = \sum_{j} \unicode{x1D7D9}(p_{i, j} > 0.5)\).

RankT5

RankT5 [9] is one of the contemporary approaches in ranking. Authors adapted the T5 [4] model to ranking problem. The approach is simple: concatenate query and document:

\[x_{ij} = \text{Query:} q_i \text{Document:} d_{ij}\]Then calculate the first hidden variable in decoder:

\[\mathbf{z} = \text{Dense}(\text{Decoder}(\text{Encoder}(x_{ij})))\]Normall, in T5, everthing is in text format. However, authors avoided this structure. They specify a special unused token in the vocabulary of T5 and take its corresponding normalized logits as ranking score.

\[\hat{y}_{ij} = \mathbf{z}_{\text{unused token index}}\]then, the objective is listwise softmax cross entropy loss

\[\ell(\mathbf{y}_i, \hat{\mathbf{y}}_i) = - \sum_{j=1}^{m} y_{ij} \cdot \log \left( \frac{\exp(\hat{y}_{ij})}{\sum_{j^-} \exp(\hat{y}_{ij^-})} \right)\]References

[1] Vaswani et al., “Attention Is All You Need” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017.

[2] Devlin et al., “BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding”, in Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019.

[3] Liu et al., “Roberta: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach”, arXiv preprint at arXiv:1907.11692, 2019.

[4] Raffel et al., “Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer” in Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2020.

[5] Nils Reimers and Iryna Gurevych, “Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks” in Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, 2019.

[6] Tianyu Gao, Xingcheng Yao, Danqi Chen, “SimCSE: Simple Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings” in onference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2021.

[7] Thakur et al., “Augmented SBERT: Data Augmentation Method for Improving Bi-Encoders for Pairwise Sentence Scoring Tasks” in Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021.

[8] Omar Khattab, Matei Zaharia, “ColBERT: Efficient and Effective Passage Search via Contextualized Late Interaction over BERT” in International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2020.

[9] Zhuang et al., “RankT5: Fine-Tuning T5 for Text Ranking with Ranking Losses” arXiv preprint at arXiv:2210.10634, 2022.

Leave a comment